DISC PROTRUSIONS

Disc Protrusion – Understanding Your Condition

Living with pain caused by a spinal disc protrusion is no way to live. Your pain may be a mild, constant ache in your spine as you go about your day. Maybe your pain registers at a five on a scale of one to 10; definitely not mild, but not gut-wrenching either. Or, your pain may fly off the charts. When you stand, a searing lightning bolt of electricity courses down your leg and your lower back muscles turn to spaghetti. You’d sit down to relieve the pain, but sitting makes your discomfort worse. What about lying down? That might help a little, but you’ll be tossing and turning all night anyway. You start to question your sanity and begin to think there is no end to your agony. Will this last forever? Is there any relief in sight?

While you may or may not be familiar with the level of severe pain described here, you should know that the majority of patients diagnosed with a disc protrusion in the neck or back usually experience mild to moderate pain, or none at all. A disc protrusion – a damaged intervertebral disc that has expanded past its typical boundaries within the spinal column – is one of many possible consequences in the cascade of degenerative changes that can take place in the spine, and the location and severity of the protrusion typically dictate the symptoms you’ll experience.

Back pain and disc protrusion can often be caused by spinal instability.

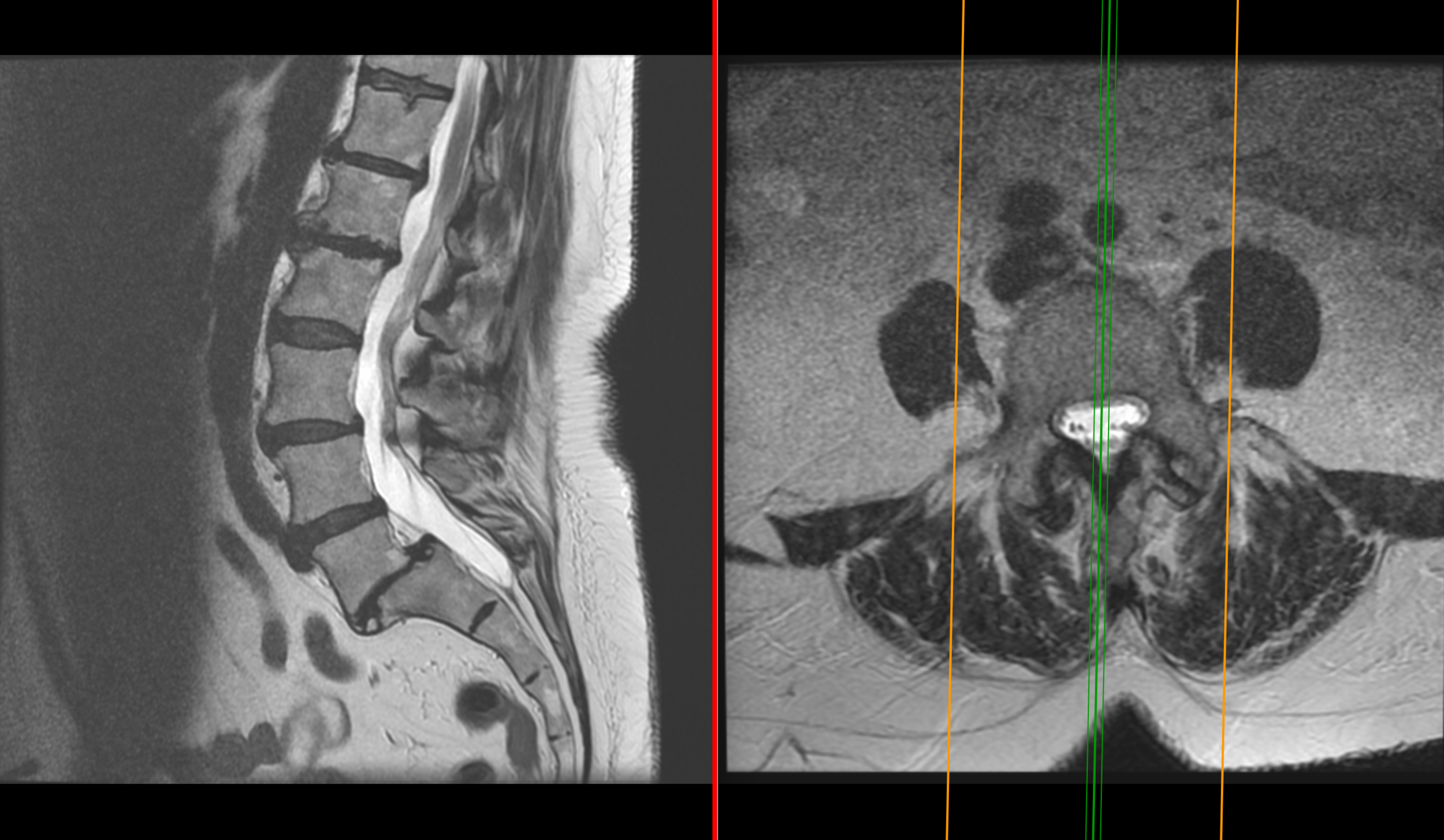

It can be an utterly helpless feeling to live with any amount of back or neck pain, but take comfort in the fact that you are not alone. More than 30 million Americans suffer from some level of back or neck pain at any given time, and almost everyone will exhibit some form of spinal degeneration on an MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) or CT (computed tomography) scan.

If diagnostic imaging has revealed a protruding disc in your neck or back, you’ll probably want answers to your burning questions, namely, “Why is this happening to me?”

Spinal Anatomy

Before we dig deeper into what a disc protrusion is and how it came to be in your spine, it will be helpful to review some basics of spinal anatomy.

Vertebrae – the bones that form the spine. Vertebrae are stacked to provide support to the body and protect the spinal cord. Generally, a human has 24 individual vertebrae: seven cervical (neck), 12 thoracic (mid-back), and five lumbar (lower back). The bodies, or cylindrical bases, of these individual bones, serve as the platform for intervertebral discs. Additionally, there are five fused vertebrae in the sacrum and three to five fused bones in the coccyx, or tailbone.

Intervertebral discs – the pliable, cartilaginous pads that lie between individual vertebrae in the spine. Discs are the spine’s shock absorbers and also help to facilitate spinal movements. Two adjacent vertebrae and the disc between them form what’s called a vertebral motion segment.

Facet joints – the pair of joints that connect two individual vertebrae at the back (posterior) side of the spine. These synovial joints help give the spine its ability to perform a wide range of movements.

Disc Protusion with spondylolistheis

Muscles, ligaments, and tendons – the flexible, supportive components of the spine. Together, these soft tissues form a complex network that helps keep the spine upright, while providing it and the trunk with the ability to move.

Spinal cord and nerves – the neural structures that transmit motor and sensory information to and from the brain and the other parts of the body. The spinal cord, which begins at the base of the brain, runs through the spinal canal (formed by stacked vertebrae) to the lower back, where it splits into a bundle of nerves known as the cauda equina. Nerve roots extend off the sides and down the length of the spinal cord and travel to the rest of the body through smaller vertebral canals called foramina.

To gain a deeper understanding of disc protrusion and how it occurs, let’s take a more concentrated look at the specific anatomy of an intervertebral disc.

Imagine an intervertebral disc in terms of a water bed. A water bed is a type of mattress that has a flexible outer shell with a liquid core. When you lay on it, instead of breaking through that outer shell and falling into the water, your weight is supported. Sandwiched between vertebrae, a healthy disc behaves similarly, with its gel-like interior (nucleus pulposus) surrounded by a pliable, fibrous outer wall (annulus fibrosus).

Annulus fibrosus – A healthy disc’s outer wall is made up of tight bands of collagen fiber, or lamellae. Each band is arranged in concentric rings around the nucleus pulposus, and the individual fibers of each lamella are oriented in 30-degree angles to the base of the disc, a pattern which alternates in successive rings. During twisting, turning, and bending movements, this unique orientation allows the lamellae fibers in one section of a disc to tense while others relax.

Nucleus pulposus – A healthy disc’s inner core differs from the annulus fibrosus in that it is not fibrous, but instead a gelatinous matrix of collagen fibers, proteoglycan protein molecules, and nearly 80 percent water. This highly relevant core matrix is responsible for absorbing nutrients into, and expelling toxins out of, a disc via the blood supply of nearby tissues. The nucleus pulposus is also what gives a disc its main characteristics of shock absorbency and flexibility, which both help to facilitate spinal movement.

Just like an old water bed that has been used for many years, the annular wall and inner core of a healthy intervertebral disc begin to show signs of age, typically starting with the disc’s loss of water content. Various small injuries (microtraumas) caused by what may seem like unnecessary spinal movements, jolts, and bumps over time, can lead to the formation of tiny fissures or tears in the annular wall. Scar tissue may then form over these fissures. The cycle of tearing and scarring can eventually damage the nerve fibers in the outer one-third of a disc’s annular wall and impede the processes of nutrient absorption and toxin removal, both of which can lead to the dehydration of the nucleus pulposus. Once the water content of a disc diminishes, the average strength of a disc’s annulus fibrosus is threatened. Weakened annular walls can spell trouble for intervertebral discs tasked with distributing forces throughout the spine. One of the many results of this weakening is a disc protrusion.

Understanding Disc Protrusion

There are many terms, some used interchangeably, and some used incorrectly, to explain disc protrusion, including “bulging,” “herniated,” “ruptured,” and “slipped.” The sheer number of terms related to disc degeneration can make anyone’s head spin and, in all honesty, they can be difficult to define accurately. In the most basic sense, all of these terms describe a disc that has shifted beyond the limits of the standard disc space, which are typically the edges of vertebral bodies.

Disc protrusion is especially hard to define without comparing its characteristics to those of other disc conditions. A protruding disc is technically a form of a herniated disc, not a bulging disc as it is commonly considered. A herniation is defined as the localized displacement of disc material that may or may not is contained by the annular wall, whereas a bulging disc is defined as a contained, circumferential expansion of disc material. To clarify further, a bulging disc, which is the most commonly diagnosed form of disc degeneration, can be compared to a hamburger that is a bit too large for its bun, with expansion occurring between 50 to 100 percent of the disc’s circumference.

Disc protrusion, on the other hand, can be compared to squeezing a balloon, where a smaller percentage of the annular wall is affected. A deteriorating disc that continues to have regular compression forces exerted on it from adjacent vertebrae is at risk for outward expansion of the nucleus pulposus, which can cause a section of annular lamellae fibers to pull apart. This can allow the inner core to project into the torn tissues and create a pocket, or bulge, along the edge of the disc. Protrusions usually place a disc at a higher risk for rupturing completely.

Additional disc protrusion specifics include:

Types – Focal protrusion affects less than 25 percent of the disc’s circumference, while a broad-based protrusion can account for 25 to 50 percent of the circumference.

Location of protrusion – A disc protrusion can occur in any section of a disc’s annulus fibrosus. This means a protrusion can occur at the posterior (back, toward the spinal cord), lateral (side), anterior (front), or even superior (top) segments of a disc. The location of a protrusion is often further classified by its proximity to the vertebral foramina, the channels between vertebrae where nerve roots exit the spinal column.

Symptoms – As mentioned earlier, symptoms can vary widely between individuals with a disc protrusion. Some may experience mild discomfort while their symptoms debilitate others. Still, others may never be in pain. This variance of symptoms will be discussed in more detail later on.

A more severe disc protrusion or herniation is called a disc extrusion, and this occurs when a portion of the nucleus pulposus pushes ultimately through a localized segment of the annular wall. This form of a herniated disc is almost always painful.

Deteriorating discs that eventually bulge or become herniated can be an indication of degenerative changes taking place in the spine that may lead to disc space shrinkage, the gradual wearing away of facet joint cartilage, the onset of facet joint disease (spinal osteoarthritis), or the formation of bone spurs.

Causes and Risk Factors of Disc Protrusion

Looking back, we’ve learned that a disc protrusion can occur as a result of a disc’s annulus fibrosus sustaining repeated microtrauma and scar tissue formation over time. We also know that this can eventually lead to the dehydration of a disc’s inner core material and significantly weaken the bands of annular lamellae to the point of tearing and bulging. With this information, it’s safe to say that the act of aging is one of the more common causes of disc protrusion. However, most cases of disc degeneration arise as a result of several causative factors combined.

Along with aging, a disc protrusion can also be caused by:

Genetics – Sometimes, the risk for developing a disc protrusion is increased if your family has a history of back and neck pain and degenerative disc issues.

Injury – Similar to the hidden microtraumas your discs sustain throughout life, traumatic injury caused by car accidents, falls, and even playing sports can exert large amounts of force on intervertebral discs, which may lead to a protrusion.

Weight – Attributing weight gain to disc degeneration may seem odd, but it’s important to remember that the spine as a whole is responsible for supporting the body. Any added stress placed on the discs, facet joints, ligaments, and muscles requires these components to work harder to carry out their supportive roles. This overcompensation, often paired with an abrupt twisting or turning motion, can lead to the eventual or immediate formation of a disc protrusion. For this same reason, pregnant women are at a higher risk for the condition as well.

Excessive stress – Obesity isn’t the only way you can “stress out” your spine. Sometimes, repetitive movements, such as lifting and placing boxes on shelves or even swinging a golf club can put added pressure on the spinal components. A disc protrusion can also arise as the result of prolonged sitting, standing, and exposure to vibrations, as when operating heavy machinery.

Lifestyle habits – Certain lifestyle choices and patterns can also contribute to the formation of a disc protrusion. An inadequate amount of regular exercise can weaken core muscles in the abdomen and back, which can affect spinal support. Poor posture can place undue stress on the facet joints and discs. Additionally, an unhealthy diet, an excessive intake of alcohol, and smoking tobacco can corrupt the strength of the discs and accelerate the dehydration process.

Symptoms of Disc Protrusion

As previously mentioned, a disc protrusion may cause back or neck pain, or remain completely asymptomatic. The symptoms you experience will usually depend on whether the disc itself is painful or the protruding disc material compresses a portion of the spinal cord or a nerve root.

Let’s take a quick look back at the formation of a disc protrusion. We know that as a disc deteriorates, small fissures and larger tears may affect the annulus fibrosus. Disc pain can become a factor if these fissures damage the nerves that innervate the outer one-third of a disc's wall. Disc nerves may be further irritated by the release of inflammatory-inducing proteins from the disc’s nucleus pulposus. Additionally, as a disc weakens, it can shift slightly (called “micro-motion”) as it attempts to maintain its opposition to spinal compression forces. The body’s response to this growing instability is to trigger muscles spasms, which in itself can cause significant pain.

You may experience an additional set of symptoms if a disc protrusion comes into contact with any neural structure in the spine. Nerve compression causes radiculopathy or radiating pain that travels the length of the affected nerve. Many individuals with a disc protrusion complain of arm or leg pain and might attempt to treat those areas specifically when a bulging or herniated disc in the spine is the real culprit. The confusion arises because the pain is referred from the area of compression down the nerve, appearing in the limbs and the other regions of the body.

If you have a disc protrusion or bone spur compressing nerves in the neck, you may experience:

Pain that travels down through the shoulder, arm, hand, and fingers on one side of the body.

Weak, spastic arm muscles.

Numbness and a tingling, or “pins-and-needles” feeling in the arm and hand. This may make holding a pen or picking up your phone or other objects difficult.

Comparably, nerve compression in your lower back may lead to the following symptoms:

Shooting pain down one side of the body, affecting the lower back, hips, buttocks, legs, and feet.

Muscle weakness and spasm in the lower back and legs.

Numbness and tingling in the thigh, calf, and foot, which can make walking difficult.

An inability or difficulty in lifting the front part of one-foot walking, known as foot drop.

Although rare, severe cervical spinal cord compression may lead to paralysis from the neck down, while significant pressure placed on the spinal cord in the lumbar spine can lead to lower body paralysis, as well as bowel and bladder incontinence. If you experience these symptoms, you should go to an emergency room immediately to be treated.

Keep in mind that most cases of a disc protrusion will be no cause for fear or panic. The earlier that a disc protrusion is identified with an MRI or CT scan – even if it isn’t causing pain – the sooner you can take steps to avoid or slow the advancement of continued degeneration potentially.

Disc Protrusion Procedures and Vertebral Motion Analysis by AOMSI Diagnostics

You may have already attempted several conservatives, nonsurgical treatments that your doctor suggested to help find relief from a disc protrusion. If you suspect a disc protrusion but your MRI shows minimal findings, having a vertebral motion analysis by AOMSI Diagnostics may be the next step for you to find answers. But if you’ve failed to find relief through any of these treatments after several weeks or months, surgery may become an option.

.